Volga Baikal AGRO NEWS Update on the Global Climate Change Impact on the Russian Agriculture !!!

Climate change and its enormous human migrations will transform agriculture and remake the world order — and no country stands to gain more than Russia.

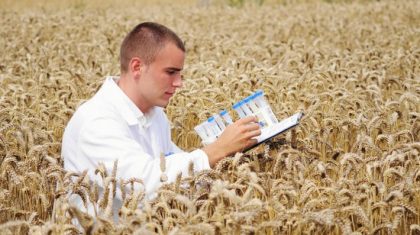

A great transformation is underway in the eastern half of Russia. For centuries the vast majority of the land has been impossible to farm; But as the climate has begun to warm, the land — and the prospect for cultivating it — has begun to improve. Across Eastern Russia, wild forests, swamps and grasslands are slowly being transformed into orderly grids of soybeans, corn and wheat. It’s a process that is likely to accelerate: Russia hopes to seize on the warming temperatures and longer growing seasons brought by climate change to refashion itself as one of the planet’s largest producers of food.

Around the world, climate change is becoming an epochal crisis, a nightmare of drought, desertification, flooding and unbearable heat, threatening to make vast regions less habitable and drive the greatest migration of refugees in history. But for a few nations, climate change will present an unparalleled opportunity, as the planet’s coldest regions become more temperate. There is plenty of reason to think that those places will also receive an extraordinary influx of people displaced from the hottest parts of the world as the climate warms. Human migration, historically, has been driven by the pursuit of prosperity even more so than it has by environmental strife. With climate change, prosperity and habitability — haven and economic opportunity — will soon become one and the same.

And no country may be better positioned to capitalize on climate change than Russia. Russia has the largest land mass by far of any northern nation. It is positioned farther north than all of its South Asian neighbors, which collectively are home to the largest global population fending off displacement from rising seas, drought and an overheating climate. Russia is rich in resources and land, with room to grow. Its crop production is expected to be boosted by warming temperatures over the coming decades even as farm yields in the United States, Europe and India are all forecast to decrease. And whether by accident or cunning strategy or, most likely, some combination of the two, the steps its leaders have steadily taken — planting flags in the Arctic and propping up domestic grain production among them — have increasingly positioned Russia to regain its superpower mantle in a warmer world.

For thousands of years, warming temperatures and optimal climate have tracked closely with human productivity and development. After the last ice age, human colonization of Greenland surged with a period of warming only to sharply contract again during a period of abrupt cooling. More recently, researchers have correlated a quickening economic pulse in Iceland with years that had above-average temperatures, just as suffocating heat waves in the global South have tempered growth. There is an optimum climate for human productivity — average annual temperatures between 52 and 59 degrees Fahrenheit, according to a recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences — and much of the planet’s far north is headed straight toward it.

Marshall Burke, the deputy director of the Center for Food Security and the Environment at Stanford University, has spent the better part of a decade studying how climate change will alter global economies, mostly focusing on the economic damage that could be wreaked by storms and heat waves and withering crops.

Productivity, Burke found, peaks at about 55 degrees average temperature and then drops as the climate warms. He projects that by 2100, the national per capita income in the United States might be a third less than it would be in a nonwarming world; India’s would be nearly 92 percent less; and China’s future growth would be cut short by nearly half. The mirror image, meanwhile, tells a different story: Incredible growth could await those places soon to enter their prime. Canada, Scandinavia, Iceland and Russia each could see as much as fivefold bursts in their per capita gross domestic products by the end of the century so long as they have enough people to power their economies at that level.

Russia has always wanted to populate its vast eastern lands, and the steady thawing there puts that long-sought goal within reach. Achieving it could significantly increase Russia’s prosperity and power in the process, through the opening of tens of millions of acres of land and a flourishing new agricultural economy.

If humans continue to emit carbon dioxide at high rates, roughly half of Siberia — more than two million square miles — could become available for farming by 2080, and its capacity to support potential climate migrants could jump ninefold in some places as a result. But!!! Not all thawed land will work; poor soils in many places won’t be arable or will require loads of fertilizer to make things grow. And the change won’t come overnight; soils in the process of thawing are an inherently unstable recipe for mayhem as roads and bridges crack and buildings collapse with the seasonal heaves and sinks of the earth. For a while, thawing regions may be nearly impassable. Eventually, though, the thaw will be complete and a new equilibrium reached that makes the land buildable and plantable again.

The wait may not be especially long. This season, crops of winter wheat and canola seed in southern Siberia produced twice the yields as the year before.

But agriculture offers the key to one of the greatest resources of the new climate era — food — and in recent years Russia has already shown a new understanding of how to leverage its increasingly strong hand in agricultural exports.

Russia is now the largest wheat exporter in the world, responsible for nearly a quarter of the global market. Russia’s agricultural exports have jumped sixteenfold since 2000 and by 2018 were worth nearly $30 billion, all by relying largely on Russia’s legacy growing regions in its south and west.

In the decades to come, as Russia’s grain and soy production rise as a result of climate change, its own food security will give it another wedge to drive into global geopolitics, should it wish to use it. Russia’s agricultural dominance, says Rod Schoonover, the former director of environment and natural resources at the National Intelligence Council and a former senior State Department analyst under the Obama and Trump administrations, is “an emergent national security issue” that is “underappreciated as a geopolitical threat.”

To American intelligence experts, two things have become clear: Certain parts of the world might one day use the effects of climate change as rungs on a ladder toward greater influence and prosperity.